‘Imperfectly Realized Analogies’. James Baldwin, Black Lives Matter and Palestine

Door Remo Verdickt, op Thu Nov 09 2023 23:00:00 GMT+0000As the war between Israel and Palestine intensifies, defenders of both parties continuously invoke prominent thinkers in their interventions. Enter James Baldwin, civil rights icon and poster grandfather of the Black Lives Matter movement. 36 years after his death, Baldwin’s critique of the Zionist policy of occupation is increasingly reinvigorated in the public sphere.

When the African American author and civil rights activist James Baldwin (1924-1987) debated the white anthropologist Margaret Mead (1901-1978) in late 1970, this entailed Baldwin’s usual verbal fireworks. The conversation came about at Mead’s request. As an icon of liberal and progressive America, Mead wanted to maximize the dissemination of her views on racism. She found the perfect format in an extensively publicized dialogue – simultaneously televised and released as an LP and book – with one of the most prominent Black thinkers of the time. Over the course of two days, Baldwin and Mead intensely debated the tensions between science and experience, religion and justice, impotence and privilege. Only one topic would halt the conversation; Israel. When Baldwin compared the structural oppression in the US with the situation in Palestine – ‘I have been, in America, the Arab at the hands of the Jews’ –, his interlocutor immediately intervened: ‘I suggest we drop this because it gets us nowhere and will get us nowhere. These are just a set of imperfectly realized analogies.’

In his book A Shadow over Palestine: The Imperial Life of Race in America (2015) cultural scientist Keith Feldman mobilizes this anecdote to illuminate the extent to which liberal America consistently has refused to even consider comparisons between the oppression of African Americans and that of Palestinians. Tellingly, Baldwin’s analogy was cut from both the televised and album-issued interview – it is only featured in the integral transcript A Rap on Race (1971). Over the past decade, Baldwin’s writings have received renewed critical and public attention thanks to the Black Lives Matter movement, the extraordinary documentary I Am Not Your Negro (2016) and an endless cavalcade of Baldwin-citations on social media. Baldwin’s political thought is gradually becoming increasingly embedded in an internationalized discourse of decolonization. Recently, the Palestinian cause has moved front and center within this multifarious dynamic of posthumous mobilization. Naturally a complete equation between two socio-political situations on different continents and in divergent time frames is not attainable, but as Feldman argues: isn’t every analogy ‘imperfectly realized’?

From ghetto to ‘occupied territory’

Baldwin’s views on Jewish identity, Zionism, and Palestine shifted throughout his career. In one of his first essays, ‘The Harlem Ghetto’ (1948), published in the Jewish American magazine Commentary, he compared the African American experience to that of his Jewish compatriots. At that time, he saw the unified Zionist project, which would result only a few months later in the foundation of the State of Israel, as a luminary for Black America. After all, by the end of the 1940s there was still no comprehensively organized civil rights movement to speak of in the US. In 1961 an official invitation by the Israeli government would somewhat adjust Baldwin’s admiration. During his visit to the nascent nation, Baldwin wrote ‘Letters from a Journey’; sketches in which he mainly acknowledges his growing ambivalence. Here he recognizes Israel’s policy of militarization – considering that the state is surrounded by ‘hostile’ countries – but he also questions the ostensible social segregation of Western and Eastern Jews. He is not (yet) able to move himself to a complete condemnation of the regime, although he admits: ‘Perhaps I would not feel this way if I were not helplessly and painfully – most painfully – ambivalent concerning the status of the Arabs here.’ It would take another decade until Baldwin practiced the term ‘Palestinians’ – the Israeli authorities were extremely successful in the consistent denial of Palestinian identity. In 1969, prime minister Golda Meir would still argue that before the foundation of the State of Israel ‘there was no such thing as Palestinians… they did not exist.’

Baldwin increasingly compared Israeli politics to the apartheid regime in South Africa.

His visit to Israel also inspired Baldwin while writing his masterpiece The Fire Next Time (1963). The book’s two essays brought Baldwin worldwide fame and crowned him the literary voice of the by now fully fledged Civil Rights Movement. The other side of the coin was that the younger generation of militants, especially the Black Power movement, started to perceive Baldwin as too socially accepted by the white establishment’s standards. From the mid-1960s onward he found himself straddled: on the one hand, now that he had acquired a seat at the table, he continued to enter into a dialogue with white America (as he did with Mead); on the other hand, he wanted to accommodate Black Power’s combatant and implacable discourse. In the same time period international awareness of the Palestinian cause was rapidly growing. Historian Rashid Khalidi identifies the disastrous Six-Day War (1967) as a catalyst for unified Palestinian nationalism. The Black Panthers, meanwhile, found themselves in a state of war with the American police and intelligence agencies. Accordingly, the FBI-orchestrated murders of activist Fred Hampton and others mirrored the actions of the Mossad in Europe and the Middle East. Baldwin, too, started to denote Harlem as ‘occupied territory’ – analogous to the anti-colonial discourse in the Third World. At the same time he critiqued (and condemned) the growing antisemitism within the African American community.

Internationalization

In the 1970s, Baldwin’s political activism internationalized. Less and less he viewed the foundation of Israel as a local political affair. Instead, he mainly discerned a cynical game of Western interests. From the censored conversation with Mead: ‘We put a handful of people at the gate of the Middle East, in an entirely hostile, embattled area where they could be murdered at any moment and we knew it, not because we loved the Jews but because we could use them.’ He condemns antisemitism but positions himself nonetheless ‘against the State of Israel because I think a great injustice has been done to the Arabs. There is no defense for their situation.’ He increasingly compared Israeli politics to the apartheid regime in South Africa. In No Name in the Street (1972) he denounced the West’s double standards when it came to international conflagrations:

What America is doing within her borders, she is doing around the world. One has only to remember that American investments cannot be considered safe wherever the population cannot be considered tractable; with this in mind, consider the American reaction to the Jew who boasts of sending arms to Israel, and the probable fate of an American black who wishes to stage a rally for the purpose of sending arms to black South Africa.

With its radical tone and sweeping internationalist scope, even today No Name is routinely considered one of Baldwin’s ‘minor’ works. Yet the book plays an important part in the author’s recent revival. For I Am Not Your Negro’s voice-over, masterfully ventriloquized by Samuel L. Jackson, director-screenwriter Raoul Peck mainly drew on Baldwin’s ‘later’ period, with No Name front and center. Peck, a Haitian cosmopolitan who alternately lived in the US, Congo and Europe, posited that Baldwin inspired him since childhood – giving Peck ‘a voice, words, and rhetoric’ in the process. ‘Baldwin knew how to deconstruct stories and put them back in their fundamental right order and context. He helped me connect the story of a liberated nation, Haiti, and the story of the modern United States of America and its own painful and bloody legacy of slavery.’ Yet it is striking that Peck leaves out the most explicitly internationalist excerpts of Baldwin’s argument from his film. Although they were thus already paying attention to his transnational message, Peck and the simultaneously ascending Black Lives Matter movement initially evoked the author in an exclusively American context.

Spirit in opposition

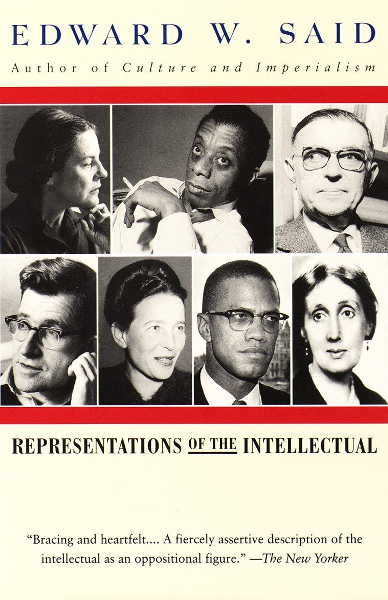

Other voices had already mobilized Baldwin in an explicitly international framework before. Thus the eminent Palestinian American academic and activist Edward Said would literally crown Baldwin the essential representation of the intellectual by placing him on the cover of his eponymous book in 1994.

In the book itself, Said claims that the work of figures such as Baldwin have shaped his own representations of intellectual conscience. Baldwin’s ‘spirit in opposition, rather than in accommodation,’ inspired Said’s activism on behalf of Palestine and against the ‘Orientalist’ Western gaze ‘because the romance, the interest, the challenge of intellectual life is to be found in dissent against the status quo at a time when the struggle on behalf of underrepresented and disadvantaged groups seems so unfairly weighted against them.’ Indeed, Baldwin had repeatedly explicitly defended those who were silenced in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. In 1979, he wrote about a political scandal concerning his good friend Andrew Young, former adviser to Martin Luther King. As the first African American ambassador to the United Nations, Young had dared to meet his Palestinian colleague without the American government’s approval. President Carter and pro-Israel politicians were infuriated and immediately forced Young to resign. The case is reminiscent of the recent dismissal of British MP Paul Bristow. Bristow, too, was fired from his post as ministerial aide because of an attempted dialogue – in his case an appeal to the British government to support a permanent ceasefire after Israel retaliated the horrendous attacks of October 7 with massive bombardments in Gaza.

Over the past few weeks, ‘An Open Letter to the Born Again’ has been busily cited on X (former Twitter).

In the wake of Young’s dismissal, Baldwin wrote the short essay ‘An Open Letter to the Born Again’ – the title refers to the evangelical Americans who unconditionally support Zionist policies. Baldwin masterfully paints the twentieth-century history of Israel and Palestine and clearly distinguishes Zionists from Jews. He concludes: ‘Finally: there is absolutely – repeat: absolutely – no hope of establishing peace in what Europe so arrogantly calls the Middle East (how in the world would Europe know? having so dismally failed to find a passage to India) without dealing with the Palestinians.’ Baldwin considers Young’s attempted rapprochement to the Palestinian Authority a moral exemplar: ‘With a silent, irreproachable, indescribable nobility, [Young] has attempted to ward off a holocaust, and I proclaim him a hero, betrayed by cowards.’

Between indictment and dialogue

Over the past few weeks, ‘An Open Letter to the Born Again’ has been busily cited on X (former Twitter). When you enter the search terms ‘James Baldwin’ and ‘Palestine’ on the medium, countless variations on the following paragraph appear:

But the state of Israel was not created for the salvation of the Jews; it was created for the salvation of the Western interests. This is what is becoming clear (I must say that it was always clear to me). The Palestinians have been paying for the British colonial policy of ‘divide and rule’ and for Europe's guilty Christian conscience for more than thirty years.

44 years down the line, Baldwin’s words remain as relevant as they were in 1979 – even though his claim ‘I must say that it was always clear to me’ is slightly revisionist. Yet it is remarkable that only this militant excerpt continues to reverberate online. The broader context of the essay, and especially its explicit call to dialogue, introspection, and empathy, meanwhile gets lost in the shuffle. This should come to no surprise, given X’s polarizing and, thanks to its character limitat, inherently unnuanced machinations. Regardless, the recent Twitter trend demonstrates how Baldwin’s posthumous reception and mobilization slowly but steadily transcend an exclusively (African) American context. This dynamic illustrates both the internationalization of BLM’s own decolonization discourse as well as its impact on comparable non-Western projects. A reciprocity between Baldwin’s legacy and contemporary world problems ensues, as forgotten writings such as ‘An Open Letter’ or the debate with Mead gain literary currency while Baldwin’s global intellectual standing simultaneously strengthens pro-Palestinian interventions.

Thus Susan Abulhawa named her most recent novel Against the Loveless World (2020) after a phrase from The Fire Next Time.

While tweeters firstly focus on Baldwin’s criticism of Western interference in Palestine, pro-Palestinian authors also pay attention to his inherently pacifist message. Thus Susan Abulhawa named her most recent novel Against the Loveless World (2020) after a phrase from The Fire Next Time. Abulhawa’s book narrates the story of Nahr, a Palestinian refugee born during the Six-Day War – just like Abulhawa herself. For nearly 400 pages Nahr is being flung back and forth between Kuwait, Iraq, Jordan, and Palestine. Everywhere she encounters the same colonial and patriarchal violence. Eventually she joins a Palestinian resistance group. In a key scene Nahr and her revolutionary lover Bilal find momentary comfort in Baldwin’s book. Baldwin’s observation that ‘to be committed is to be in danger’ continues to haunt them. When Bilal asks if Baldwin’s peaceful plea means that they should also love the Israeli, Nahr answers:

I don’t think that’s necessarily what Baldwin is saying. I think he just means that we should fortify ourselves with love when we approach them. It’s more about our own state of grace, of protecting our spirits from their denigration of us; about knowing that our struggle is rooted in morality, and that the struggle itself is not against them as a people, but against what infects them—the idea that they are a better form of human, that God prefers them, that they are inherently a superior race, and we are disposable.

Abulhawa’s novel firmly sides with the oppressed Palestinians and has little understanding for the Israeli policy of occupation. Yet it is of note that protagonist Nahr explicitly evokes Baldwin in a rare recognition of the oppressors’ shared humanity. Ultimately, both Baldwin and Nahr know that it is precisely the acceptance of this shared humanity that constitutes the condition to effectively combat oppression. That analogy entails constructive potential – no matter how ‘imperfectly realized.’