For us, by us: MMK’s Crip Time from a disabled perspective

Door Lisa Jansen, Eline Pollaert, op Thu Jun 30 2022 22:00:00 GMT+0000Disability is a shortcoming. At least, that is how the world sees it – including the art world. Lisa Jansen and Eline Pollaert, however, know better. In a society relentlessly expecting physical and mental achievements, everyone comes out on the losing end eventually. Together they visited the exhibition Crip Time. They reflect about their experiences and what society should and could learn from disabled artists.

The exhibition Crip Time, which was on display between September 18, 2021 until January 30, 2022 at the Museum für Moderne Kunst in Frankfurt, gives free rein to a new world. A world in which interdependence is the norm, in which health is a collective matter, in which vulnerability is celebrated. A world created by artists who are themselves disabled, sick and mad. Instead of bending our bodies and minds to the clock, they use ‘crip time’ to bend the clock to our needs. It’s not us who need to be fixed, it’s the world. What does it mean for two disabled art lovers to see this vision come alive?

Welcome to the realm of disability

Upon entering museum, we are greeted by London. She is the dog of artist Emilie Louise Gossiaux. Two versions of London, made from papier mâché, face each other standing on their hind legs. Their front legs are extended, as if they are inviting you to grab them and commence waltzing. The two dog figures seem to play a sphinx-like role as guardians to the crip realm (crip being a reclaimed slur from the world ‘cripple’). In between the dogs there is two meters of free space, enough to grant entrance to everyone who wishes to enter the realm. Were it not that in order to get there, one must climb stairs. We take the elevator.

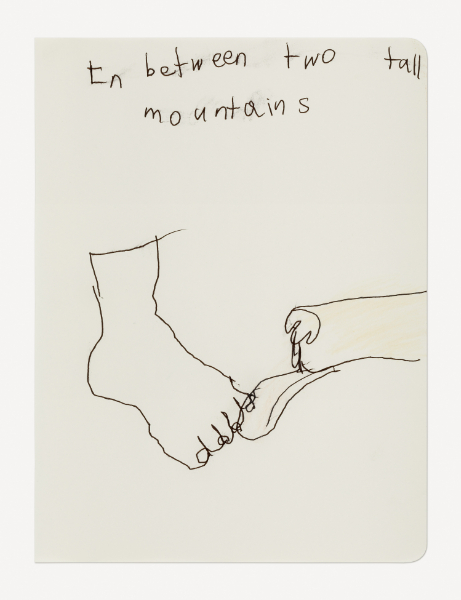

A couple of meters ahead, I – Lisa – find London again. This time drawn in pencil on familiar, cream-colored paper with rounded corners on one side of the sheet. I’m thinking of my own Moleskine agenda full of meetings and to do’s. The sheets are made from the exact same material. Until my eyes start filling up with tears. Gossiaux’s work forces me to be present in the here and now. Dog London looks at me across her shoulder. Her body is drawn with just a few black lines of ballpoint pen on paper, but it’s like she looks straight at me.

Within the crip community, interdependence is a central concept. We are all dependent on one another in some way. With us, disabled folks, it’s just more visible.

I think of my own dog Mila, of how she enlarges my world that is made so small by disability and ableism. Of how I’m not just there for her, but how I can tell she’s there for me as well. Of how we communicate without words and seem to understand exactly what the other means. Of how we found a shared language that works. From the ten drawings, Gossiaux and London seem to have the same connection. Sometimes the human and dog figures are so intertwined that only one figure remains.

Gossiaux is blind and London is her guide dog. But the Labrador is so much more, as Gossiaux’s work featuring London shows. Within the crip community, interdependence is a central concept. We are all dependent on one another in some way. With us, disabled folks, it’s just more visible. Nondisabled and not yet-disabled folks are interdependent as well, even though our society prefers to think otherwise. Independence is a farce. There is only togetherness.

The drawings London licks my hand and In between tall mountains depict loving, everyday scenes between human and dog. The last drawing brings a smile to my face, because I recognize the wet dog tongue tickling in between Gossiaux’s toes. Some things are meant to be shows two paw-hands that meet each other in the middle, above them the aforementioned words – the ballpoint pen staining the paper. I sigh deeply. Some things are meant to be. That’s right.

Multi-colored black

The title of the exhibition, Crip Time, underscores for me – Eline – an important daily experience. The expression crip time describes the way disabled folks experience time. For people like me, time sometimes passes slower and sometimes faster. Daily activities and navigating inaccessibility take more time, while impairments can shorten our lifespans. The concept crip time is also the lens through which I look at the work of Derrick Alexis Coard, of whom the exhibition features twenty drawings.

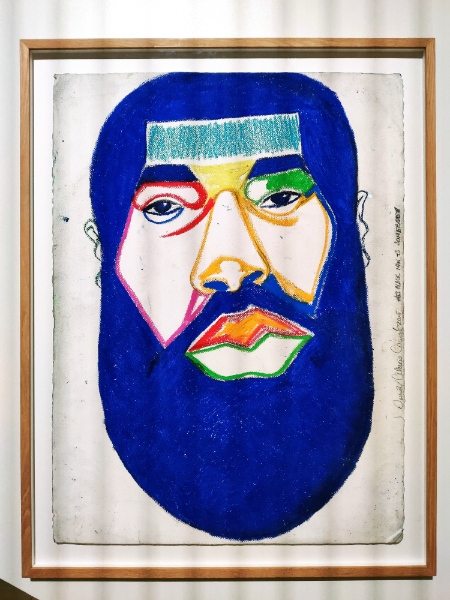

In his teenage years, Coard spent a lot of time on closed psychiatric wards due to his schizoaffective disorder. Hospitalizations like those literally pause your life; others determine the rhythm of the days. In 2017 Coard died of a heart condition at the age of 36. He was outrun by time. Or not? The corner space of MMK’s first floor is filled with Coard’s colorful portraits of Black men with full beards and powerful facial features. No self-portraits, but expressions of his own experiences congealed in time. His time. Crip time.

Museums have other bodies than mine in mind when they set up their exhibitions, both in terms of ability and size.

One of the drawings, like Coard’s other works, consists of a portrait of a Black man. With accurate lines and plain surfaces he sketches a frontal face with full lips, a straight nose and a large beard. The hair on his head and face is dark blue, the rest of the face is drawn in red, green, orange, pink, yellow and light blue. The depicted man appears neutral. He looks straight at me, with a relaxed and somewhat fatigued look in his eyes. Along the edge of the A4-paper, a handwritten text says: ‘David Alexis Coard, 2015. This Black Man is Somebody.’

Looking at this portrait, I realize that Coard reclaims not only his own humanity, but other Black men’s humanity too. They are overrepresented in the North-American legal system – he lived his whole life in Brooklyn, New York. Black men are convicted five times more than white men. Two in five inmates are disabled, particularly cognitive impairments and psychiatric conditions are prevalent. The legal system is set up against Black disabled men. Coard knows this. With his portraits, he not only puts a face to himself and others like him, but he also claims Black disabled men’s right to exist in all their complexities.

This space is ours

As a disabled, neurodivergent and fat person my – Lisa’s – relationship to museums is complicated, to say the least. I feel distanced from art, I’m afraid that I’m not ‘smart’ enough to understand it, I don’t feel welcome in exhibition spaces. Museums have other bodies than mine in mind when they set up their exhibitions, both in terms of ability and size.

That is why I think Shannon Finnegan’s work ‘Do you want us here or not?’ resonates with me so deeply. Their benches can be found in various spots in the museum. They offer resting places to visitors in the Crip Time expo. The benches are a deep cobalt blue. That is no coincidence. Think of the wheelchair symbol: a white stick figure in a rudimentary wheelchair against a bright blue background. The benches are all decorated with slogans in Finnegan’s typical handwriting: ‘It was hard to get here. Rest if you agree.’ Or: ‘This exhibition requires me to stand for too long. Sit if you agree.’ On one bench, the letters spell: ‘I would like to spend more time with this piece, but standing hurts. Sit if you agree.’ I take a seat.

I see Finnegan’s benches as a form of crip protest. They claim a piece of hostile, inaccessible spaces as ours.

Thanks to this bench, I was able to experience Coard’s aforementioned work at my own pace. Normally my body is continuously screaming for relief: a seat, a railing. The discomfort my body experiences through walking and halting constantly, prevents me from calmly taking in the exhibition object. The fact that I was able to observe a room full of art in peace, felt strange and like coming home simultaneously.

I see Finnegan’s benches as a form of crip protest. They claim a piece of hostile, inaccessible spaces as ours. But I also notice the irony of being happy about the presence of these benches. Without them, I would have been unable to experience the exhibition. At the same time, the benches would have been redundant if the museum had offered adequate seating in the first place. You could say the same about the exhibition as a whole: does it not only have a right to exist due to the fact that the museum space is not yet ours?

A sea of blue

Like Shannon Finnegan, Chloe Pascal Crawford refers to the color blue in her installation For the 12 disabled people in Lebenshilfehaus (Area of Refuge). I – Eline – step into a room of only a couple of square meters, which is only accessible via stairs. Or not, because wheelchairs, rollators and other walking aids cannot access it. Across the stairs hangs a curved safety mirror, so that mobility impaired visitors can still see the room. This barrier is a conscious choice. In her work, Crawford regularly plays with the (in)accessibility of the world around us. She emphasizes that accessibility concerns all of us.

Azure blue waves reach up the walls of Crawford’s installation, to about 1,5 meters high. The white walls and the stairs remind me of a swimming pool. However, the title reveals that I’m not in an innocent paddling pool. When Germany, Belgium and the Netherlands were hit by the largest floods in decades in July 2021, twelve disabled people in the German province of Rheinland-Pfalz drowned in a nursing home. The tidal wave struck so quickly that the only employee present was unable to save anyone residing at the ground floor.

The title of the installation hits me. This is a memorial for a tragedy which took place only six months prior. Inaccessible architecture is a literal question of life and death. In times of emergency, (natural) disaster and war disabled people are the first to be left behind. Inaccessibility is violence. Area of refuge is an accusation against society’s indifference.

For us, by us

The stories told by the artists in Crip Time are universal. The World Health Organization calculated that 1 in 5 people are disabled. Anyone who lives long enough is confronted with changing physical and mental abilities. Our society stigmatizes illness and disability. Just like the reclaimed term crip, the exhibition reclaims the richness and resilience of the disabled experience. We form communities with our own cultures, histories and philosophies. Our bodies and minds hold both pain and pride. They are breeding sites for innovation and creativity. Crip Time is a milestone and a beacon of hope, both for disabled folks and not (yet) disabled folks.

In an art world that increasingly speaks of the importance of ‘diversity’ and ‘inclusion’, Crip Time holds up a mirror.

For us, Lisa and Eline, this was the first time that we as art lovers visited a place that was specifically designed for us. Where a fundamental aspect of who we are is not merely tolerated, but acknowledged and even celebrated. This realization brings us joy and sadness at the same time. After surviving a pandemic in which disabled people are left as ‘dry wood’ again and again for over two years, this exhibition offers literal breathing room. To share that experience with a loved one was no less than formative. In an art world that increasingly speaks of the importance of ‘diversity’ and ‘inclusion’, Crip Time holds up a mirror. It is our deepest wish that this exhibition is one step towards a new world. A world that acknowledges disabled bodies and minds as guardians of timeless wisdom.