Bodies of knowledge: how we can learn more from each other

Door Sarah Vanhee, op Tue Oct 22 2019 00:00:00 GMT+0000If we ask ourselves how art schools can better relate to a changing world, one of the first issues to address is knowledge transfer itself. What do we really mean by ‘knowledge’? And what assumptions lie behind the Western idea of passing on this knowledge? We asked artist Sarah Vanhee to share her reflections on her bodies of knowledge (BOK) project, a study of less directed forms of shared knowledge exchange. It may be an inspiration for art schools.

What does bodies of knowledge (BOK) exactly mean? The complexity of knowledge exchange starts with my attempts to explain this practical study in a comprehensible way. In my imagination, I see a place for the exchange of alternative, non-dominant knowledge emerging in towns and cities. But who would be drawn to this idea and who wouldn’t? Communication is performative.

I say to my 4-year old son: ‘In your school you have your own classroom, don’t you? Well, I’m making a classroom like yours for grown-ups. Where grown-ups can learn things from each other, for example at Place Flagey [in Brussels].'

I wanted to create a kind of place where learning is a positive experience, where people can learn from each other.

In Manchester I was speaking to a diverse group of young people, aged between 17 and 22, and I said: ‘When I was young, I didn’t like going to school. I wanted to learn, was quite curious about many things, but sitting in the classroom immediately killed my thirst for knowledge. I really didn’t understand why we had to sit still for eight hours, with all those hormonal changes going on in our bodies, listening passively to uninspired teachers who always told only one side to a story. Is this growing up? I didn’t want my son to have that sort of learning experience. That’s why I wanted to create a kind of place where learning is a positive experience, where people can learn from each other, outside of our little bubbles. Not from books, but from what we know as a result of our lived experience.’

Whenever this is explained to artistic partners, usually in writing, it reads as follows: ‘BOK is a place for the exchange of non-dominant, underexposed and/or suppressed knowledge, an intergenerational and inclusive space (by sometimes also being exclusive). BOK subverts dominant ideas about what knowledge is and how it can be exchanged, thereby helping to create a socially just society which generates possibilities instead of exploiting lives, in a world that includes both the human and the non-human.’ This description is inspired by concepts proposed by G. C. Spivak, Achille Mmembe, Audre Lorde, Donna Haraway, Grada Kilomba, N. El Sadaawi, bell hooks, Tagore and many others.

In my PhD application, I was not allowed to write a running text: I had to abbreviate most of the words and include as many references as possible: ‘BOK investigates how public space can be activated through artistic intervention for the transfer of non-dominant (forms of) knowledge. How can we create a “safe space” within the public space for the exchange of various forms of suppressed knowledge among diverse members of civil society? What artistic and political strategies can be used to overturn the knowledge/power relationships within the public domain? (See also ARIA Summer School: ‘Making Public Domain’).'

The higher we climb in the dominant intellectual order, the more scientific, cryptic and opaque the language becomes.

These four descriptions reveal a typically Western hierarchy, where oral transmission seems to be less truthful than written knowledge. What is written or spoken of in the first person seems to be less serious than a description where the subject is absent: an objective opinion carries more weight than a subjective opinion.

The higher we climb in the dominant intellectual order, the more scientific, cryptic and opaque the language becomes. The more details in terms of references and sources (especially if they are white and male), the more credible the text.

In Teaching to Transgress (1994), bell hooks points out how limited and limiting this ladder of values really is: 'It is easy to imagine different locations, spaces outside academic exchange, where such theory would not only be seen as useless, but as politically nonprogressive, a kind of narcissistic, self-indulgent practice that most seeks to create a gap between theory and practice so as to perpetuate class elitism. (…) Hence, any theory that cannot be shared in everyday conversation cannot be used to educate the public.'

bodies of knowledge therefore seeks to be a place where the relationship between ‘theory’ and ‘public’ can unfold with all the necessary space and time for ‘every-one’: young people, old people, people with fragile mental health, people in precarious living conditions, etc.

How do you ensure truly horizontal knowledge sharing?

BOK will take place in Brussels from autumn 2020 and will run for at least two years. It is a collective project, supported by a wide range of individuals, communities and organisations, and is currently led by a core of three women from Brussels aged between 30 and 40 with differing cultural, social and professional backgrounds: Nadia, Flore and Sarah.

Who will do the talking?

How will this theory translate into practice? Last summer we carried out a month-long pilot version in Manchester upon invitation of the British arts organization Quarantine. A brief report of this will provide a good picture. How do you ensure truly horizontal knowledge sharing?

In the weeks before the actual ‘learning day’ we spoke to people in Manchester spontaneously, in the street, in the library, at events and so on, using small performative tools to enter into conversation with them about the knowledge that they already had or would like to acquire.

Previously, we had developed a ‘little learning book’ containing basic questions, such as: ‘What would you like to un-learn?’ ‘What is a moment of learning you will never forget?’ A second series of questions came from a long list of ‘bodies of knowledge’ that we were looking for, topics that people might be able to give us information about – not ‘how do I mend a flat tire?’ but for example: ‘How to disrupt vicious systems that have been normalized’, ‘Which rituals (from the past) should we learn and take up again?’, ‘Who taught you to feel good?’, etc. People could also add a question of their own, as our participant Toby did: ‘I would like to learn who really rules the world today.’

We are trying to challenge the dominant order of speaking up in society.

If people said that they knew something about a subject, we asked them whether they would like to come and share this knowledge during the learning day. We invited them on the basis of what they knew, not on the basis of their official status or function. The framework for this was what Xochitl Levyo Solana, professor at the CIESAS Institute in Mexico, calls ‘sentipensar’ or ‘sensingthinking’: ‘doings that I have called in academic grammar “other knowledge practices”’(this is stated in her paper ‘Undoing colonial patriarchies’ in the collection Decolonization and Feminisms in Global Teaching and Learning, 2019). This ‘knowledge’ can therefore also take the form of a (physical) practice.

Occasionally we uninvited some individuals after an initial conversation, because we feared that they might only deliver a monologue, that they might incite discrimination or violence, or because they already had access to various public fora.

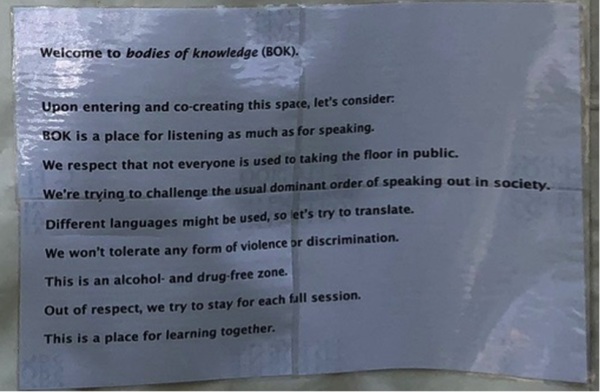

Principally, we were not selective in who we approached, but we always kept the BOK intentions in the backs of our minds (‘We are trying to challenge the dominant order of speaking out in society’). Experience in public speaking was not a requirement. Nobody needed to be able to speak ‘perfectly’. We did not ask about their identity or background.

Open access

The circumstances in which you share knowledge are at least as important as the knowledge exchange itself. For the learning day we erected a tent in St Johns Gardens, one of the few green spaces in the city center of Manchester. A tent is the simplest form of ‘enclosure’ where people can come together.

Inside the tent, chairs were placed in a circle, the archetypal arrangement for a gathering where all co-learners are equal and there are no fixed hierarchies. To make this space accessible to all, one entrance remained open at all times and there was no charge for any of the sessions. In this way, you also appeal to passers-by, as happened in Manchester when a young man wandered in on his way to the station. There was also free childcare for people with children. At the entrance, we hung a brief explanation, describing the program and intentions of this ‘nomadic class’:

Provided that people could agree with these BOK intentions, anyone could participate, think and share as a ‘learner’. However, free access for everyone is not always desirable. We restricted access to some sessions (for example, access only for people who identified as a woman), if this would enable us to guarantee a safe space for those people.

Oral knowledge exchange was central within this space, and the speaker was not separated from the spoken word, nor the listener from the speaker. There was no teacher or pupil – we were all ‘co-learners’. Listening to people who differ in terms of gender identity, social, cultural and religious background, age, bodies, mental and physical health, character, lived experience, etc. is a transformative experience. We feel that we are being addressed not only cognitively, but also emotionally and physically. This may be referred to as ‘deep listening, deep talking’ – an empathetic practice.

The relationships between the co-learners changed all the time, depending on who they were, how they spoke and what they were talking about. For example, there was a lovely moment when a whole group of adults was listening to two young people, Maham and Ahmed, who were sharing their views on ‘(mental) health in young people, by young people’.

At the learning day in Manchester, most of the time people first listened empathetically; questions and comments followed later, and the discussion was never hijacked. We regard this as an important aspect of BOK: respect for anyone who dares to speak in public, shared responsibility within the group, encouraging thinking together. Moderation is rarely necessary. Even a Libyan woman who had only been attending English lessons for six weeks had the courage to speak in this environment. If translation was required, we relied on the collective translation abilities of the group.

There seems to be a thirst and a desire to exchange knowledge that you cannot acquire from books or YouTube.

‘A fantastic environment for listening, learning, thinking and feeling,’ said Maria afterwards. Richard was also pleased with the exchange. ‘It worked at a clear and visible political level in relation to a kind of educational commonism, and also had real artistic depth and stratification.’ Sarah particularly emphasized the fact that the environment was right. ‘I liked the fact that this felt like a supportive and safe space where you could share your ideas – even if you disagreed. I really enjoyed hearing people speaking from their own experience about such a wealth of different knowledge and experience.’

We, too, were very happy with our first learning day. Not only because a diverse and changing group of people actually showed up, who collectively had created a wide range of ‘deep learning’ experiences. Above all, the project felt necessary: there definitely seems to be a thirst and a desire to exchange knowledge that you cannot acquire from books or Youtube, but where it is necessary to physically come together. It became clear to us that BOK must be a structural and sustainable platform, which can be present in the city for the long term, and can be recognized and populated by many people as a place for alternative knowledge exchange.

‘As if I was born in a world without trees’

''I well remember the surprise and annoyance of an experienced headmaster, reputed to be a successful disciplinarian, when he saw one of the boys of my school climbing a tree and choosing a fork of the branches for settling down to his studies. I had to explain to him that ‘childhood is the only period of life when a civilized man can exercise his choice between the branches of a tree and his drawing-room chair, and should I deprive this boy of that privilege because I, as a grown-up man, am barred from it?’ What is surprising is to notice the same headmaster’s approbation of the boys’ studying botany. He believes in an impersonal knowledge of the tree because that is science, but not in a personal experience of it.(…) And as far as my personal behaviour goes, I have been obliged to act all through my life as if I were born in a world where there are no trees.' (Tagore, The English writings of Rabindranath Tagore – essays, 2007)

Does our official schooling really do what it was designed to do? My own experiences in that area reflect those of Tagore. During the 1990s I attended a conventional secondary school in West-Flanders [Belgium]. The school management was relatively open-minded. There were at least a few inspiring teachers who – regardless of the subject – managed to engage the students and make them think, or who took a personal interest in somebody.

But in general I experienced school as a system which was obliged to routinely train us in reproducing theory and had little to do with our lives. Teachers who could not impose their authority were mocked. Students who showed too much interest were not popular.

The only student with a working class background at my art school was forced to give up her studies after a year.

After secondary school I did not go to university because I thought – rightly or wrongly – that I would end up in a detached knowledge factory. Because of my much more positive experiences with my extra-curricular poetry and drama tutors, I decided to do something in the direction of acting (not knowing, at the time, that you could also study ‘art’). I wanted to learn something that would make me feel awake and real, something that wasn’t all about excellence and competition.

I followed courses in Belgium and the Netherlands. The former entirely negative, the latter positive. I hope the Belgian schools have changed in the positive sense in the meantime, but during my time we were mainly taught by people who had just missed a role in Thuis [a Belgian soap opera], or who had been appointed to a permanent position many years ago but who no longer practiced in art.

The tutors were predominantly men, while 95% of the students were women. They were all white, cis, ‘healthy’ and slim. The only student with a working class background was forced to give up her studies after a year. The only tutor who really engaged was unfortunately also the one who gave classes in his bedroom.

Later, in Amsterdam, I fortunately found myself in a pedagogically responsible environment, with committed tutors who had practical experience and was able to set out along my own track. It was headed by a woman who did not exert her authority but provided a listening ear for many people.

Throughout my time at art colleges I engaged in independent study in parallel, and also in practical projects through various social engagement initiatives.

Throughout my time at art colleges I engaged in independent study in parallel, with research in philosophy, sociology, ethics, law, and so on, as well as in practical projects through various social engagement initiatives. Of course, I remained a dilettante at everything. Through lived experiences and friendships I learnt that I could articulate and transform my intuitive resistance to social injustice and distorted patriarchal power dynamics, and that I could try to use my privilege as a white, highly educated, ‘healthy’ woman to help bring about social change. Gradually I learnt that art and life cannot be separated.

For all these reasons, I believe that it is important that BOK will now run for two years in the city where I live: in Brussels, where connections already exist. Work and life have always been very closely linked in my artistic practice, in the same way that art, citizenship and humanity are linked. But now I want to be able to give that ‘locally anchored’ work a more substantial and structural dimension.

Here in our own city we hope to activate the potential for a ‘commoning’ of alternative knowledge exchange by unlocking and connecting various ‘bodies of knowledge’. We will achieve this in a semi-nomadic way: BOK will be located in the same square or park in one of the communes of Brussels for several weeks or months at time, then will move on. In this way we will create a ‘place’ which will travel slowly within the public ‘space’ of the city.

From humanistic geography, I learned that, 'space' and 'place' are important concepts’, and they do not have the same meaning. 'Space' is something abstract, without any substantial meaning. While 'place' refers to how people are aware of/attracted to a certain piece of space. A place can be seen as space that has a meaning.

BOK and art

‘But is BOK art?’ To me, this question is irrelevant. I am doing this project as an artist, and art is still the only context in which I can do something like this. More specifically, it is part of a doctorate in the arts at ARIA (Antwerp Research Institute for the Arts) on shared oral knowledge transfer.

'An artist is anyone who considers their activity as art, independent of canons, art critics, museums, Wikis and any other 'specialist' schemas.'

That is the paradox: if you want the necessary support and resources for a plan, you have to legitimise it as art. And that means meeting the established art world’s demand for output, documentation, and to a certain extent quantifiable results and specific authorship.

I myself wrestle with this. With regard to artistic practice, I follow the view of the Zapatistas, as described by Batallones Femeninos in the collection Global Teaching and Learning (2019): 'an artist is anyone who considers their activity as art, independent of canons, art critics, museums, Wikis, and any other 'specialist' schemas that classify (that is, exclude) human activities.' However, the aim of BOK is what, in principle, moves a great deal of art. It arises from the radical idea of claiming public space as a place for alternative knowledge exchange. ‘Radical’ here means: with plenty of time for meeting, care and listening – a soft form of radicalism.

As an artist, choosing not to generate products but to create encounters, to engage socially, to introduce new forms of ‘public’, has now gained a permanent place within internationally established circuits. Examples of this include the work of Tania Bruguera, Jonas Staal, Thomas Hirschhorn and Jeanne Van Heeswijk.

BOK is not about exploiting excellent work for individual success, recognition or profit. And the artistic process is not a hygienic operation within a comfort zone out of which a watertight product crystallizes. We want to create connections within local communities, based on rich knowledge which does not have to be a ‘resource’. The ‘commons’ that we work with are not ‘commodities’: they are not necessarily tangible or marketable.

We find it impossible to transfer theory which is, as it were, detached from the world.

In this vein, we also want to operate invisibly to a large extent, so that we can guarantee people a ‘safe space’. Because not everyone feels comfortable ‘in the spotlight’, and for some people this can even be dangerous.

BOK is definitely not alone in making these choices. The practices, organisations and movements which inspire me the most, where individual authorship is not an issue, are long-term and local. In Brussels, these include Le Space, Mémoire Coloniale, Noms Peut-Être and Bamko. Each of these, in its own way, works on the transfer of non-dominant knowledge. Art or not, it’s all about what they share.

Towards a polyversity

With this in mind, it is hoped that the philosophy and politics of BOK will inspire the institutional sphere of universities and conservatoires. Through BOK we aim to take issue with ‘conventional ideas on theory as what “illuminates” practice’ (Xochitl Leyva Solana in Decolonization and Feminisms in Global Teaching and Learning) and to opt for theory which is ‘embodied’, as the authors of the feminist anthology This Bridge Called My Back named it back in 1981.

According to this vision, it is impossible for us to teach theory without any consequences for a lived practice, to transfer ideas which are, as it were, detached from the world – which often is still the case in universities today. There is no knowledge transfer without subjectivity.

Art schools should be able to work on their accessibility as a place where the world comes together, thereby increasing their social relevance.

If BOK relates to universities in any way – for it is also a place where knowledge is exchanged – it should be through the idea of extending the UNI-versity to a POLY-versity, as Achille Mmbembe once advocated in his lecture 'Decolonizing knowledge and the question of the archive':

‘A pluriversity is not merely the extension throughout the world of a Eurocentric model presumed to be universal and now being reproduced almost everywhere thanks to commercial internationalism. By pluriversity, many understand a process of knowledge production that is open to epistemic diversity. It is a process that does not necessarily abandon the notion of universal knowledge for humanity, but which embraces it via a horizontal strategy of openness to dialogue among different epistemic traditions.’

Art schools, in turn, should be able to work on their accessibility as a place where the world comes together, thereby increasing their social relevance. As a place where artists meet in their social, political and magical role, rather than as a stepping stone towards a profession. ‘Learning’ then means developing what potentially already exists, and transforming it based on an open imagination using the available and new tools, skills and methodologies.

It is essential for art schools to become places that are free of fear, stripped of problematic power relationships.

It is essential for art schools to become places that are free of fear, where audacity, courage and experimentation are encouraged, stripped of problematic power relationships. Where decolonization and feminism are not agenda items, but form the core principles of a radically different culture, politics, organization and representation within the institution.

Using one’s imagination and being creative in converting this imagination into reality – regardless of (artistic) medium – then automatically becomes a political act.

We never stop learning. In my radical imagination, a project like BOK which materializes in the city can bring us closer to a tangible future where a school becomes a place for ‘the practice of freedom’ (bell hooks). Where the exchange of knowledge is central, with a love of learning, where we learn in order to understand, understand in order to develop, develop in order to be free, so that we can act and live in freedom.