A New Bauhaus? The Debate for a More Inclusive Europe

Door Rolando Vázquez, Hicham Khalidi , op Thu Jan 14 2021 18:00:00 GMT+0000Ursula von der Leyen launched the idea of a 'New European Bauhaus' to involve artists and scientists in the European Green Deal. Rolando Vázquez and Hicham Khalidi have doubts on that dubious name. 'A Europe that responds to the climate crisis is also a Europe that addresses inequality and discrimination: we need a name that validates this idea.'

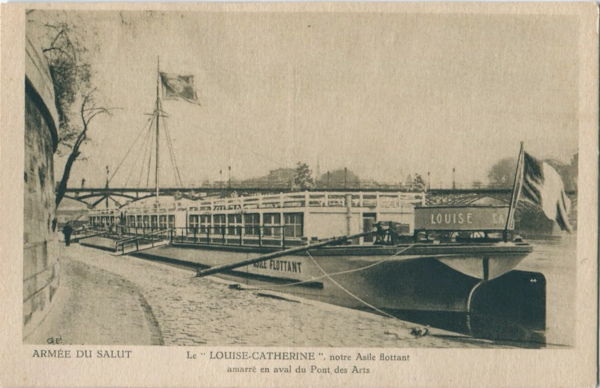

For nearly a century, the reinforced concrete barge Louise-Catherine remained mostly moored along the Seine river in the heart of Paris. Originally christened Le Liège, it first hauled coal from Rouen to Paris. Then in 1929, with funds from American Singer sewing machine heiress Winnaretta de Polignac, the Salvation Army commissioned modernist architect Le Corbusier to transform the boat into a floating homeless shelter that would remain in use until 1994. Only in 2018, when rising water levels flooded the Seine’s banks, was the boat tilted against the wharf, sinking it to the bottom of the river within minutes.

As Amitav Ghosh writes in his book The Great Derangement (2016), the effects of climate change are difficult to grasp and even harder to fictionalize in art or literature. Nevertheless, Le Corbusier’s capsized shelter is a powerful image of the limits and paradoxes of modernism and its objective to design a better and beautiful world. The story of modernism cannot be separated from the history of coloniality. The design for a better world was underpinned by colonial domination and extraction. Today we are becoming increasingly aware that modernity is sinking beneath the ecological devastation and social divisions it unleashed. Le Corbusier's sunken barge offers us a concrete metaphor for modernism’s failed project in the face of climate collapse.

On September 16, 2020 the European Commission, under the stewardship of President Ursula von der Leyen and First Vice President Frans Timmermans, launched an ambitious and historic initiative to fund innovative scientific and artistic endeavors to abate climate change and allow Europe to meet its goal of zero net carbon emissions by 2050. The Commission intends to bring the European Green Deal to life by creating ‘a collaborative design and creative space, where architects, artists, students, scientists, engineers and designers work together (…) to combine sustainability with good design’ within and beyond Europe’s borders. Drawing on the heritage and language of modernism, this initiative has been coined the New European Bauhaus.

Naming a new European cultural Green Deal after the Bauhaus School is not only non-inclusive and Eurocentric, it goes against the very core of what climate thinking should be about.

While we support the EU Commission’s bold undertaking, which invites cultural actors to forge change through an interdisciplinary approach to art, design, technology, and science, we find it unfortunate and misinformed to name it after the Bauhaus School. Founded in 1919 by Walter Gropius in Weimar, the Bauhaus reconceptualized art, craft, and industrial design. While revolutionary for its time, the school was deeply inegalitarian. Women were barred from most workshops and the institution paid little heed to care of the Earth. Over time, the Bauhaus became linked to an industrial capitalism that engendered social and ecological injustice across the globe. We continue to live its consequences today.

Naming a new European cultural Green Deal after the Bauhaus School is not only non-inclusive and Eurocentric, it goes against the very core of what climate thinking should be about. An initiative that seeks to foster open and just societies must be committed to intersectional equality along the axes of gender, race, and class. It must also overcome the one-sidedness of Eurocentrism, which stifles active engagement within and among Europe’s plural societies and undermines the possibility of mutually enriching intercultural engagements with others around the world. So too must it overcome the anthropocentrism that has made of Earth a disposable resource upon which modernity’s dreams were built.

What’s in a Name?

A name opens or forecloses possibilities. A name includes or excludes histories. Naming is and was a tool deployed to control the imaginaries of societies. It is an epistemic technology that inserts itself in places: one which represents while it erases, which determines who owns or who belongs while disavowing others. The act of naming is more than a superficial form of branding. It is akin to producing monuments. Today such monoliths are being contested across the world. They stand, and fall, as symbols of imperialism and colonialism and grave injustice. Current social movements are challenging monuments that remain inserted in public spaces, in academic institutions, and in museums. These movements contest an economy of representation that glorifies the history of the victor, which has been the history of patriarchy and empire and the history of colonialism and genocide.

Naming the EU’s pivotal historic initiative is a political act with significant political implications. The New European Bauhaus appends itself to a problematic modernist legacy that, at best, affords only a partial understanding of Europe and overlooks the mounting climate crisis. It sanctions the very social and political inequities and environmental injustice that the European Green Deal is determined to address.

New Bauhaus and the Traps of Modernism

Bauhaus is the story of the increasing fracture between initial ideals of utopian, spiritual, and artistic freedom on the one hand and growing utilitarian industrial functionalism on the other. The cleft deepened in 1922, when the School split into two camps, and crystallized further in 1933, when it was shuttered by the Nazis. It was in exile in Chicago that Mies van der Rohe brought Bauhaus utilitarianism to full fruition with the creation of the International Style. Cold, spare lines built from ‘new materials and rational aesthetics’ became an emblem of what Tom Wolfe would call a ‘Utopia Limited.’ What resulted was, in the words of Christopher Turner, ‘an architecture and design that was co-opted by big business and became the corporate language of power.’

Bauhaus proclaimed itself a harbinger of progress and enjoying the good life. But this so-called good life was predicated on the subjugation of other life-worlds.

Bauhaus propagated the industrialization of European design and luxury (by way of companies such as Vitra) as well as its consumerist democratization (by way of conglomerates like IKEA). It also laid the foundations for information technology and sensory perception, which through big data, has led to the crisis of privacy and data sovereignty we face today. The school proclaimed itself a harbinger of progress, of designing and enjoying the good life. But this so-called good life was predicated on indiscriminate extraction and the subjugation of other life-worlds.

Modernism ascribed to a Eurocentric modern/colonial order. This order was marked not only by political and economic subjugation but by control of knowledge and aesthetics. Eurocentrism, which attributes universal validity to its notions of beauty, enjoyment, and necessity, is inseparable from the exploitation, denigration, and erasure of others’ worlds of meaning.

A new European Bauhaus reanimates the modernist pretension to govern the aesthetics and define the standards of a good life. The name is limited to a Eurocentric narrative in which a reduced notion of Europe and European thought is the norm. Europe, in turn, is reduced to a singular and static geographic and historical entity instead of a dynamic web of events, histories, memories, cultures, ideas, and desires of the people who inhabit it. Europe is a fluid plurality, composed of manifold experiences, voices, and histories. It is an articulation of differences that cannot be reduced to a dominant monoculture.

The losses of cultural diversity and biodiversity arrived hand in hand with modernity. The Western project of civilization was forged through Eurocentrism and anthropocentrism. While Eurocentrism has caused the demise of other cultures, of other worlds of meaning, anthropocentrism has meant the exploitation of Earth. Earth has become an Other to the human. It has been reduced to a pool of resources to be classified, extracted, and consumed by the human.

Just as Eurocentrism is not hindered by borders, the devastating impact of Europe’s ecological policies are not confined to the continent alone. The result is the loss of the Earth’s heritage, of species, and of cultures. It is the loss of Earth-worlds. As their existence is truncated, so too are our collective possibilities into the future.

We will not be able to design our way out of a climate crisis. What we need is a transformation of our ethics of life and our forms of social engagement.

Earth’s most marginalized populations are experiencing defuturing—to borrow the expression of Tony Fry—most acutely with the loss of their territories, environments, and the possibilities of inhabiting their own worlds. Today many are becoming economic and climate refugees. Climate change exacerbates global inequities. Pollution and environmental destruction intensify gender, racial, social, environmental, and economic injustices. Regions that produce the least CO2 output bear the worst brunt. As UN Secretary General António Guterres said in his remarks at Columbia University in December 2020, ‘As always, the impacts fall most heavily on the world’s most vulnerable people. Those who have done the least to cause the problem are suffering the most. Even in the developed world, the marginalized are the first victims of disasters and the last to recover.’ The Covid-19 pandemic has revealed and exacerbated these rifts within and between societies along the lines of economic inequality, racism, sexism, and ageism.

The European Green deal must recognize Europe’s ecological impact within and beyond its borders. An understanding of modernity that does not take into consideration the condition of earthlessness it has created is not only partial and insufficient but complicit with the loss of Earth. A Eurocentric and anthropocentric mindset is incapable of finding thorough and real solutions. We need to become decolonially and intersectionally aware of structural inequalities brought forth by modernism and by the hubris of a ‘modern design’ that has affected and continues to affect disproportionately the livelihoods of indigenous peoples, women, people of color, workers, differently abled people, and other minoritized groups as well as all those who are at their intersection, such as women of color.

Opening Possibilities

We will not be able to design our way out of a climate crisis. What we need is a transformation of our ethics of life and our forms of social engagement. Culture can set the stage to bring about these changes, but only if we begin from a recognition of what has gone wrong in legacies that prioritize profit over social wellbeing. Any overhaul or shift of the scaffoldings still upholding modernity must include other forms of economy and ways of production that take into account the numerous cultures that have been erased, are being erased, or are being denigrated. From a multiplicity of voices, we should strive to build a forum in which our plural histories and dreams can find a place and be valued.

We appeal for more horizontal structures to reorient the cultural European Green Deal toward a truly transparent and plural process in collaboration and consultation.

Numerous struggles are already being waged to contest monuments and names that celebrate colonialism. These contestations are not merely symbolic. They carry a strong demand to allow other histories to be unsilenced. Our critique of invoking the Bauhaus for a supposedly broad European initiative inscribes itself in these struggles to move beyond a limited, monocultural understanding of Europe and toward one that acknowledges and cherishes the pluralities that enrich its societies. Our critique of Eurocentrism is not a critique of Europe, but an appeal to treasure and nurture the diverse continent on which we live. It is the very basis for democratic participation in an ecological project that can benefit us all.

Ursula von der Leyen has proposed to commission five projects in five different EU countries. These initiatives should not be decided top-down. Instead, they should be guided by the participatory and open forms of governance to which we all aspire. We appeal for more horizontal structures, such as civic assemblies and town hall meetings, to rename and reorient the cultural European Green Deal toward a truly transparent and plural process in collaboration and consultation with those likely to be most impacted by its outcomes.

Let us begin this broader discussion with a conversation about the implications of the New Bauhaus title and the possibility for an alternative that conveys the myriad voices and histories comprising Europe today. We need a name that empowers the idea that a Europe responsive to climate collapse is a Europe that addresses social inequality and intersectional forms of discrimination. We need a name that results from a process of listening and participation. This, we believe, can bring about a transformative movement for an environmentally sustainable, plural, and socially just Europe.